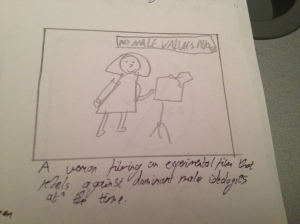

Storyboard 1

Script 2

The history of women is the film industry is an extremely interesting one. At one time, in any production the screenplay was likely to have been penned by a women, as was the continuity script. A female director may have guided the female star, who often worked for her own production company. Some women did it all. Lois Weber, the most famous female filmmaker of this period, was a screenwriter, actress, director, and producer, often on the same project. A women may have then edited the film, a female exchange owner may have distributed it, and a female manager might have exhibited it in her theater. When film was still a new medium, companies such as Universal embraced women directors, and in 1917, 8 out of 113 Universal directors were women.

This changed sooner than expected, with the invention of sound in 1928 as studios no longer wanted women directors, as they did not trust them with films that were not silent and were big business.

In the 1930s, unions and guilds were firmly established in Hollywood, with predominantly male membership. Women directors generally could not be found again until the 60s and 70s, and even then their films were usually alternative and outside the studio system. Only Dorothy Arzner survived the transition between silent film and sound films, and was the only women to sustain her career as a director for 30 years.

In the 70’s, although most female filmmakers made alternative, independent films, they took this role upon them and resisted dominant male cultures. This was after a battle starting in the 1940s to get female filmmakers in work again, with their initiatives to make personal experimental films outside the Hollywood system.

In the 1970s to 80s organisations such as Women Make Movies and Women in Film and TV UK were set up, and continue today as opportunities to network, have mentoring systems, and help with production and distribution. As well as this, the The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University has since been set up to help with statistics on women currently in the industry, along with other initiatives such as the Celluloid Ceiling Report, and competitions such as “Females First”, funding work from the best female directors worldwide.

However, statistics show women directed just 4.7% of Hollywood studio films from 2009-2013. The independent film figures aren’t much better, showing they produced just 10% of films during that period. But why is it in 2013 that female directors have directed only 6% of films? Not only this but there has been no improvement in the last 20 years, with the percentage of female crew members having decreased between 1994 and 2013.

The UK and the rest of the world isn’t much better:

– Canada has found that just 6% of feature film funding has been allocated to female directors

– Only one in 98 Nordic films released in 2012 had a women working on them

– Of independent UK films released between 2010 and 2012, 11% of the directors were women.

Although some countries do have more positive statistics such as:

– 20% of Swedish films have been made by women

– In the Middle East, female filmmakers are getting more recognition as 42% of all grants since 2010 have been to women. It is thought that this is because “Women are challenging oppression, inequality and corruption – from this, stories are born”.

-West Berlin has emerged as a center for feminist film production and cinema studies. There in November 1973 the first German women’s film festival and workshop was held.

And back in the UK, help is at hand:

Script 1

Women in the film Industry are in trouble. As recent statistics show, women directed just 4.7% of Hollywood studio films from 2009-2013. The independent film figures aren’t much better, showing they produced just 10% of films during that period. But why is it in 2013 that female directors have directed only 6% of films? Not only this but there has been no improvement in the last 20 years, with the percentage of female crew members having decreased between 1994 and 2013.

Let’s start at the beginning. When film was still a new medium, companies such as Universal embraced women directors, and in 1917, 8 out of 113 Universal directors were women.

In fact, in any production the screenplay was likely to have been penned by a women, as was the continuity script. A female director may have guided the female star, who often worked for her own production company. Some women did it all. Lois Weber, the most famous female filmmaker of this period, was a screenwriter, actress, director, and producer, often on the same project. A women may have then edited the film, a female exchange owner may have distributed it, and a female manager might have exhibited it in her theater.

But the optimistic future for women in film came to a head, sooner than they could have predicted. Even Alice Guy Blanche, the world’s first female filmmaker and creator of over 1000 films, only lasted in her position until 1920, and as the 1920’s progressed and the invention of sound in film began in 1928, studios no longer wanted women directors, as they did not trust them with films that were not silent and were big business.

In the 1930s, unions and guilds were firmly established in Hollywood, with predominantly male membership. Women directors generally could not be found again until the 60s and 70s, and even then their films were usually alternative and outside the studio system. Only Dorothy Arzner survived the transition between silent film and sound films, and was the only women to sustain her career as a director for 30 years.

In the 70’s, although most female filmmakers made alternative, independent films, they took this role upon them and resisted dominant male cultures. This was after a battle starting in the 1940s to get female filmmakers in work again, with their initiatives to make personal experimental films outside the Hollywood system.

In the 1970s to 80s organisations such as Women Make Movies and Women in Film and TV UK were set up, and continue today as opportunities to network, have mentoring systems, and help with production and distribution. As well as this, the The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University has since been set up to help with statistics on women currently in the industry, along with other initiatives such as the Celluloid Ceiling Report, and competitions such as “Females First”, funding work from the best female directors worldwide.

Across the world

– Canada has found that just 6% of feature film funding has been allocated to female directors

– Only one in 98 Nordic films released in 2012 had a women working on them

– 20% of Swedish films have been made by women

– In the Middle East, female filmmakers are getting more recognition as 42% of all grants since 2010 have been to women. It is thought that this is because “Women are challenging oppression, inequality and corruption – from this, stories are born”.

-West Berlin has emerged as a center for feminist film production and cinema studies. There in November 1973 the first German women’s film festival and workshop was held.

Back here in the UK:

Animation Variants with Sound

As previously decided, the sound I am going to use will be music that accompanies the animation of the infographic. However, if I was to approach the project in another way, I could use different music and sound effects to accompany my information. For example, I could do this by adding sound effects when text bounces onto the screen, to give the animation a more light-hearted feel. This is possible to get online, and I have found a sound effect for this called “Jump” (Koenig, 2014). I could also have approached only one topic for the animation and selected music that only accompanies this aspect. For example, if I were only to animate women who were oppressed by their lack of available roles in film, I would only use darker music and sounds, whereas if I decided to animate solely the history of women I could show this by approaching in the the typical silent film way, and having the animations of women doing slapstick comedy style directing, etc. In this case I would be using typical sounds from the silent era. However, I plan to use a bit of each so as to show the whole picture of the progression of women behind the scenes in film.

Reference List:

Koenig, M. (2014). Bounce Sounds | Free Sound Effects | Bounce Sound Clips | Sound Bites. [online] Soundbible.com. Available at: http://soundbible.com/tags-bounce.html [Accessed 22 Dec. 2014].

Sound Effect and Music Choices and Justifications

The first type of music I will be using is upbeat music, so as to show how well women were doing in the film industry before the late 1920s and invention of sound in film. For this I will be using a copyright free silent film score found online, called “Hypermusic” (Incompetech.com, 2014). This is because I think it is a fairly playful and happy song, and will capture the feel of what the industry was like during those years. It will then go into another copyright free silent film score called “Iron Horse-distressed”(Incompetech.com, 2014), which will not be played for long, but long enough to suggest that something has gone badly from the initial film system to when the Hollywood studio system first takes over. I will also use the famous “Dun dun dun” sound effect (YouTube, 2012) when this is first announced, in keeping with the tone of the infographic up to that point. I will then start using another copyright free song called “Oppressive Gloom” (Incompetech.com, 2014) which seems appropriate as a lot of the infographic has to do with the oppression of women in film, but I will not use this for the rest of the infographic, as there are positive influences and statistics along with the negative ones, which call for a song more like the copyright free “Perspectives”(Incompetech.com, 2014), which is a calm but uplifting song, which will show that there is some hope for women in the film industry yet. I would especially like to use this for information about current organisations that help women get into the film industry.

I do not intend to use many sound effects, other than the initial Dun, dun, dun one which I previously stated. This is because, although I do want aspects of the infographic to be upbeat, I would mainly like to portray it as authentic, and I think the animation and music, along with my script, will be enough to do this without the use of sound effects. However, I like the drama of the sound effect that I am using, and the fact that it is recognised for such, and so I think it will be appropriate to use in my infographic without undermining the message.

Reference List:

Incompetech.com, (2014). Royalty Free Music. [online] Available at: http://incompetech.com/music/royalty-free/?genre=Silent%20Film%20Score [Accessed 22 Dec. 2014].

Incompetech.com, (2014). Royalty Free Music. [online] Available at: http://incompetech.com/music/royalty-free/index.html?feels%5B%5D=Mysterious&feels%5B%5D=Somber [Accessed 22 Dec. 2014].

Incompetech.com, (2014). Royalty Free Music. [online] Available at: http://incompetech.com/music/royalty-free/index.html?feels%5B%5D=Uplifting&page=1 [Accessed 22 Dec. 2014].

YouTube, (2012). DUN-DUN-DUUUUN!!! Sound Effect. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bW7Op86ox9g [Accessed 22 Dec. 2014].

Final Statistics to Include

Statistics on the State of Women and Hollywood

FILM

Women directed 4.7% of studio films from 2009-2013

Women directed 10% of independent films from 2009-2013

2013

Women Behind the Scenes

- “Women were 16% of the directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers, and editors working on the top 250 domestic grossing films.

- Women directed 6% of the films.

- Women wrote 10% of the movies

- Women comprised 15% of all executive producers.

- Women accounted for 25% of all producers.”

- Women comprised 17% of all editors.

- Women accounted for 3% of all cinematographers.

- Women comprised 2% of all composers.

- Women accounted for 23% of production designers.

- Women comprised 4% of sound designers.

- Women accounted for 9% of all supervising sound editors.

- Women comprised 2% of all special effects supervisors.

- Women accounted for 5% of all visual effects supervisors.

Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film

2012

Women Behind the Scenes

- “Women were 18% of the directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers, and editors working on the top 250 domestic grossing films.

- Women directed 9% of the films.”

- Women wrote 15% of the movies.

- Women comprised 17% of all executive producers.

- Women accounted for 25% of all producers.

- Women comprised 20% of all editors.

- Women accounted for 2% of all cinematographers.

Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film

2011

Women Behind the Scenes

- “Women directed 5% of the top grossing films.”

- Women wrote 14% of the top grossing films.

- “Women comprised 18% of all executive producers.”

- “Women comprised 25% of all producers.”

- 20% of all editors were women.

- 4% of all cinematographers were women.

Stats from the Center for Study of Women in TV and Film

2010

Women Behind the Scenes

• “Women directed 7% of the top 250 grossing films.”

• Women wrote 10% of the top 250 grossing films of 2010

• “Women comprised 15% of all executive producers.”

• “Women comprised 24% of all producers.”

• 18% of all editors were women.

• 2% of all cinematographers were women.

Stats from the Center for Study of Women in TV and Film

2009

Women Behind the Scenes

- “Women directed 7% of the top 250 grossing films.”

- Women wrote 8% of the top 250 grossing films.

- “Women made up 23% of all producers”

- 18% of all editors were women

- 2% of all cinematographers were women.

Center for the Study of Women in TV and Film, San Diego State U.

2008

Women Behind the Scenes

- Only 6 of the top 50 grossing films (12 of the top 100 films) starred or were focused on women.

- “Women comprised 9% of all directors.”

- Women accounted for 12% of writers.

- “Women comprised 16% of all executive producers.”

- “Women accounted for 23% of all producers.”

- Women accounted for 17% of all editors.

- Women accounted for 25% of production managers.

- Women comprised 44% of production supervisors.

- Women accounted for 20% of all production designers.

- Women comprised 5% of sound designers.

- Women accounted for 5% of supervising sound editors.

- Women comprised 1% of key grips.

- Women accounted for 1% of gaffers.

- Women comprise only 23% of film critics at daily newspapers.

- Women comprised 22% of directors working on films appearing at the major film festivals compared to 9% on top grossing films.

- Women accounted for 19% of writers working on films appearing at festivals but only 12% on top grossing films.

- Women accounted for 33% of producers working on films appearing at festivals but only 20% of those working on top grossing films.

- Women comprised 23% of editors working on festival films compared to 17% of those working on top grossing films.

- Women comprised 9% of directors of photography working on festival films but only 4% of those working on top grossing films.

- Overall, women comprised a larger percentage of behind-the-scenes workers on documentaries than narrative features. Of all behind-the-scenes individuals working on documentaries, 29% were female and 71% were male. Of all behind-the-scenes individuals working on narrative features, 18% were female and 78% were male.”

2007

Behind the Scenes

- “In 2007, women only comprised 15% of all directors, executive producers, writers, cinematographers, and editors working on the top 250 grossing films.”

- “In 2007, only 6% of the top 250 grossing films were directed by women.”

- In 2007, only 5 of the top 50 films starred or were focused on women.

Sundance Research for Film Screened at the Festival From 2002-2012

- “29.8% of filmmakers (directors, writers, producers, cinematographers and editors) were female.”

- 23.9% of the films in this study were directed by women.

- Films directed by women feature more women in all roles. There is a 21% increase in women working on a narrative film when there is a female director and a 24% of women working on documentaries.

- Females direct more documentaries than narrative films – 34.5% vs 16.9%.

International Study of Films Released Worldwide (G,PG, PG-13 films released 2010-2013)

- The Center found that women accounted for 16 percent of all directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers and editors for the top 250 domestically made films in 2013. That reflects a 2 percent drop since 2012 and a 1 percent decline from the 1998 rate. Hovering at 25 percent, the count of women producers was unchanged, according to the study, which, for the first time, also took a census of female composers, production designers, sound designers, special effects supervisors, supervising sound editors and visual effects supervisors.

-

In terms of behind-the-scenes absence in those categories, 99 percent of films had no female special effects supervisors; 97 percent of films had no female composers, sound designers or sound editors; and 91 per cent had no women as visual effects supervisors.

The most gender balanced position is the producer in the Swedish and Danish sectors.

In an extended list of the critics’ Top 250 Films of All Time only 7 were directed by women.

-In 2012, only five of the top 100 films at the Australian box office had a female director. Just one of these films was solely directed by a woman, the other four were co-directed by a man.

– Of the 20 top grossing films of 2011 in Germany (accounting for more than 20 million sold tickets) only 1 was directed by a woman.

Around 20% of all the feature films made in Sweden are by women.

Only 29 percent of feature films granted funding by SFI (Swedish Film Institute) in 2009 were directed by women.

-Between 2000 and 2009 women directors were responsible for 23 percent of feature film debuts in Sweden.

In over 80 years only one woman has ever won the Academy Award for Best Director – Kathryn Bigelow (2009 – The Hurt Locker).

At the 2010 and 2012 Cannes Film Festivals there were no women directors shortlisted for the Palme d’Or. The highest number of women directors who have been shortlisted is four (20%), in 2011.

-Even more worryingly, women accounted for just 7.8% of directors on UK films in 2012, a decrease of more than 7% year-on-year (15% in 2011).

- Women make up only 23% of crew members on the 2,000 highest grossing films of the past 20 years.

- Only one of the top 100 films in 2013 has a female Composer.

- In 2013, under 2% of Directors were female.

- The only departments to have a majority of women are Make-up, Casting and Costume

- Visual Effects is the largest department on most major movies and yet only has 17.5% women

- Of all the departments, the Camera and Electrical department is the most male, with only 5% women

- Musicals and Music-based films have the highest proportion of women in their crews (27%).

- Sci-Fi and Action films have the smallest proportion of women (20% and 21% respectively).

- The films with the highest percentage were “Mean Girls” and “The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants” (42%).

- The most male crews were “On Deadly Ground” and “Robots” (10% female).

- There has been no improvement in the last 20 years. The percentage of female crew members has decreased between 1994 (22.7%) and 2013 (21.8%).

- The three most significant creative roles (Writer, Producer and Director) have all seen the percentage of women fall.

- The jobs performed by women have become more polarised. In jobs which are traditionally seen as more female (art, costume and make-up) the percentage of women has increased, whereas in the more technical fields (editing and visual effects) the percentage of women has fallen.

-In fact, in 1994 the average percentage of women on a film crew was 22.7% and by 2013 it had actually shrunk slightly to 21.8%.

-There are many reasons why the under-representation of women in the film industry could be seen as a problem. These include female crew members finding it harder to get hired/paid, employers selecting workers from a pool that is half the size it should be, fewer female role models for aspiring creatives and, of course, justice/ equality/ fairness.

-Other than cinematographers, none of the major job types saw a rise, with only producers holding steady at 25% – itself the biggest category for women. Production designers and editors were the next largest percentage share for women, at 23% and 17%.

– Independently produced films, which typically have lower budgets and skirt Hollywood hierarchy, have consistently kept the door ajar, if not fully open, to women. The findings, based on more than 9,000 credits at 23 film festivals from March 2013 to April 2014, were similar to a previous study in 20011/12. The 26% figure was a modest advance from the 24% recorded in 2008/9.

-The report showed that rather than improving over time, the number of women working with blockbuster film crews in 2013 actually declined from previous years, to an average of just 21.8%. Fewer than 2% of the directors of the top 100 grossing films last year were female and only one had a woman to compose the score.

-Visual effects, usually the largest department for big feature films, had an average of only 17.5% of women, while music had just 16%, and camera and electricals were, on average, 95% male.

My Primary Research questionnaire:

- 80% of women said they would like to go into the media industry, while 20% said no, as they thought it would be too hard to progress in.

- However, 75% of men said they would, and 25% said they didn’t know.

Interestingly, the results didn’t seem to be conclusive about whether people thought there were as many opportunities in the media industry for women as for men:

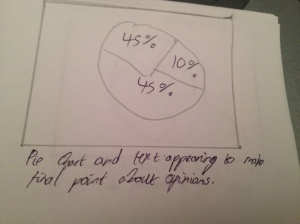

- 45% of people said there are as many opportunities

- 45% of people said there aren’t

- 10% said they didn’t know

When asked to name 3 Female film directors/producers 5 people skipped the question, which is 25% of people. Of those who did answer 3 said they didn’t know any (15%), 4 people could only name one (20%) while 7 of those answers were actresses who were also directors (35%), which could show a trend. However, 45% of people could answer with 3 female directors/producers which is more than I expected.

When asked to name 3 Male film directors/producers only 2 people skipped the question (10%) 5% of people only named one male film director and another 5% naming only 2, with no one answering the question to say they didn’t know any. This means that 80% of those interviewed knew the names of 3 male directors.

When asked if 75% of blockbuster crews being male shows an equality problem in the industry:

- 65% said yes

- 25% said no

- 10% said I don’t know

Finally, the last question on what kind of infographic people would rather watch had very similar answers and did not give a conclusive result.

- 26.32% said The current status of women in film

- 26.32% said Gender equality in film

- 26.32% said The history of women in film

- 21.05% said Feminist filmaking

“At their most numerous in 1917, 8 out of 113 Universal directors were women (about 7 percent), and Universal credited them with slightly more than 6 percent of its films. Overall the average of titles credited to women for the years 1916-19 is lower, about 4 percent. Intriguingly, however, women were concentrated in feature films, as opposed to the large volume of shorts and serials Universal released. In the same three-year period, the studio assigned 12 percent of its’ Bluebird brand feature films to the direction of women. “

“In the 1990s, Directors Guild of America statistics demonstrate, the industry paid women to direct between 7 and 9 percent the days worked in film production. Martha Lauzen’s survey of credits shows that in the early twenty-first century the proportion of women-directed titles declined from an anomalous high of 11 percent in 2000 to 5 percent in 2004 and had rebounded to 6 percent in 2007.”

I plan to include these statistics in my infographic as graphs, so that I can include as many statistics as possible and compare them to past years, without it being boring to watch.

Research to be Included in Infographic

As my questionnaire did not show a majority on what kind of infographic people would be interested in seeing, I will include a bit of each topic; from the history of women in film, to their current status, and how that relates to gender equality and feminist filmmaking. I will try to use as much quantitative data as possible without making the infographic boring, as that is the most statistically backed up and informative data. As part of this I will also be using my questionnaire to show the primary research I have undertaken. However, I will also use some qualitative data to show people’s opinions, which seems as if it will generally be from books and online, although hopefully the Women in Film and TV group will get back to me and I can use some of what they say in the email interview.

As this film will be about 3 minutes long and I cannot include all of my research, here are the most important things that I have found:

Research from “Online Secondary Research: History of Women Filmmakers- Alice Guy Blanche” and “Online Secondary Research: History of Women in Film”

- Alice Guy Blaché (1873-1968), the world’s first woman filmmaker, was one of the key figures in the development of narrative film. From 1896 to 1920 she directed hundreds of short films (including over 100 sychronized sound films and twenty-two feature films), produced hundreds more, and was the first – and so far the only – woman to own and run her own studio plant (The Solax Studio in Fort Lee, NJ, 1910-1914).

- She wrote, directed, or produced more than 1,000 films. At age 23, she was one of the first filmmakers to make a narrative movie. She pioneered the technology of syncing sound to film. She created the first film with an all African-American cast. And she was the first woman to build and run a film studio.

- Jodie Foster and Penny Marshall stand as proof that some women manage to find funding and support from Hollywood executives, but both have had to use their acting as leverage in the decision-making process.

- Women directors face a lack of support not only as a result of their gender, but also because they have a remarkable tendency to choose controversial or difficult subject matter.

- Some women directors wish to make films that employ newly defined heroines or that reverse gender expectations.

- Ida May Park, another woman among many who directed in the 1920s, refused her first job directing, thinking it an unfeminine job. Even contemporary women directors find the notion of a feminist approach to filmmaking incompatible with their need for acceptance in the industry.

- The recently deceased Shirley Clarke refused invitations to womens film festivals, even if she agreed that women directors should be recognized. French filmmaker Diane Kurys finds the idea of womens cinema negative, dangerous, and reductive, at the same time claiming, I am a feminist because I am a woman, I can?t help it.

- In the 1970s, 1980s, and the 1990s, there has been an international rise in the number of women filmmakers, both independent and studio directors.

- In the 1960s many women directed personal experimental films.

- The 1940s were a fertile time for experimental women filmmakers. In this era, Maya Deren and Marie Menken introduced many of the ideas and forms of experimental avant-garde cinema. In Britain, Joy Batchelor created animated films. In France, Jacqueline Audry directed glossy studio-produced films. In the Soviet Union, Wanda Jakubowska pioneered many of the Soviet ideals of the social document film. In Mexico, Matilde Landeta fought to direct her own productions after having served as an assistant director for many, many years. She managed to direct a few of her own projects despite the sexism of the industry.

- By the 1930s there were fewer and fewer women directors. Film was beginning to be viewed as an art form and as a powerful medium in the marketplace. Many women directors left the field when it was clear that society no longer approved of women working in such a high-profile job that clearly indicated power in the public sphere.

- Many women directors of color worked outside the studio system as independent producer/directors. African American women directors such as Eloice Gist and Zora Neale Hurston developed and introduced the independent personal film.

- By the time of the first Academy Awards, women directors had already been pushed out of many behind the scenes roles and were therefore notably absent from the awards outside of Best Actress. One exception is Frances Marion who won an award for Best Writing Achievement for her film The Big House (1930) and became the first woman to win an award for an achievement other than acting.

-

Women had always been welcome in the writing departments of many of the studios because screenwriting was an anonymous job and because writing had long been an acceptable occupation for women.

-

Paramount Studios also sought to capitalize on the ability of women to legitimize early film. Their star female director was Dorothy Arzner. Arzner began her career as a stenographer at Famous Players-Lasky, which later became Paramount. She was later promoted to film editor (a common job and stepping stone for women in the film business), and in 1927, directed her first film. When other female directors were pushed out of the business in the late 1920s, Arzner was the only woman who continuously directed films in the Hollywood studio system of the 1930s.

-

Weber’s position as a woman played a large part in allowing her to make films about risky subject matter. Just as theater owners courted female patrons to legitimize their businesses, the film industry sought female directors to legitimate the very product of film. Movies directed by women automatically carried greater moral weight. Therefore, directors like Weber could explore controversial topics under the guise of moral and social reform.

- In 1915 Weber joined Universal Studios, and in 1917 she established Lois Weber Productions, with Universal working as her distributor. Unfortunately, most of the films that Weber made while on her own did not find critical or commercial success,

-

In 1913 the company closed down, but Blaché continued to direct for her husband until 1922,

when she returned to France with her children after her marriage failed.Though her career as a director faded, she is still remembered not only for being a pioneering woman in film, but for helping to shape the early film industry.7

Research from “Online Secondary Research- Organisations and Projects 1 and 2”

- Women in Film & TV (UK) is the leading membership organisation for women working in creative media in the UK, and part of an international network of over 10,000 women worldwide.

- We host a variety of events throughout the year, present a glamorous awards ceremony every December, and run a mentoring programme for women in the industry. We also host networking evenings, collaborate with industry bodies on research projects and lobby for women’s interests.

- Any female professional working in the film, television or creative media industry in the UK can become a member of WFTV (UK). This includes a broad range of occupations, such as director, writer, producer, actor, media lawyer, accountant, broadcaster, presenter, development exec, marketing and PR exec, journalist, technician, post production, distribution, senior exec, etc.

- In 1989, a group of women came together for the first official WFTV (UK) meeting. They were a mix of business executives, creatives and performers, including Linda La Plante, Dawn French, and Janet Street Porter. These were successful women who were fed up with the still male-dominated industry which demanded they be engaged in a constant struggle to be heard and respected.

They resolved to take positive action and follow in the footsteps of organisations in LA and New York, which had been established in the 70s, to support women working in the film and TV industries. They did this by creating a network of members and organising workshops, events, mentoring and awards to help them progress in their careers.

-

By raising the visibility of women’s present and past relationship to cinema and television we aim to:

- ensure women’s work is recognised in the writing of screen histories.

- make a case for the preservation and availability of women’s films and television programmes

- increase programming choice in film theatres, television channels, DVD outlets

- encourage new approaches to film and television that are sensitive to gender, class and race

- impact on the teaching of screen media in schools and colleges

- raise the aspirations of young women who might seek careers in the media.

Facts About Women Make Movies

- “WMM has more than 500 films in its collection, representing more than 400 filmmakers from nearly 30 countries around the globe.”

- “In the last decade, WMM has worked with dozens of local women’s organizations in Asia, Latin America and the Middle East to support new International Women’s Film Festivals.”

- “WMM has returned more than $1.5 million in royalties to women filmmakers over the last three years.”

- The Women Make Movies’ Distribution Service is our primary program. As the leading distributor of women’s films and videotapes in North America, Women Make Movies works with organizations and institutions that utilize non-commercial, educational media in their programs.

- Women Make Movies also offers a unique Production Assistance Program which provides fiscal sponsorship, low-cost media workshops and information services to independent media artists. The services included in this program reflect Women Make Movies’ commitment to outreach and development of both emerging and established women film and video makers. More info.

- Women Make Movies was established in 1972 with the specific mission of training women to become film and video makers. Through the 1970s and early 1980s, hundreds of women participated in Women Make Movies’ training programs, collectively producing 70 films and videotapes. During the late 1970’s, in response to the lack of distribution and exhibition opportunities for women’s films, Women Make Movies initiated its distribution service, began presenting on‑going screenings in New York, and sponsored two international women’s film festivals.

- ABOUT US (SWIFT – Savannah Women In Film & Television, 2014) SWIFT is an organization of professional women from all realms of Film and Television. SWIFT is dedicated to networking, collaborating, mentoring and attracting a wide variety of productions to Savannah.

- Profile with resume on the SWIFT website

- Access to private Facebook page

- Monthly meetings with programs about film and television in Savannah.

- Networking with other female film professionals in Savannah.

-

Find out about projects coming to Savannah

-

The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University is the most widely cited and trusted source of information on the representation of women in film and television. For more than a decade, researchers affiliated with the Center have provided individuals working in the entertainment industry and members of the public with extensive and forward-thinking research on the employment of women.

-

Scholars at the Center conduct an extensive agenda of original research documenting women’s under-representation and investigating the reasons for the continuing gender inequities.

– agnesfilms.com is named in honor of Agnès Varda, the French filmmaker who has been making women-centered fiction films and documentaries for over 50 years. Varda, in spite of the high quality of her work, remains an obscure figure to mainstream audiences around the world. This is not surprising, since the film industry is not always supportive of women who want to work behind—as opposed to in front of—the camera.

• Foster a community of women filmmakers, scholars, instructors who teach film and filmmaking, and film lovers who support each other. We hope to be joined by men who are interested in films made by women, as well as male filmmakers, scholars, and filmmaking/film instructors. Our aim is for our community to be diverse in terms of race, class, and sexual orientation.

• Shed light on the work of talented and committed women filmmakers working today, who, like Varda, don’t have the visibility they merit.

• Provide a space where filmmakers and scholars come together to discuss their crafts and learn from each other, fostering project collaborations and strong connections between these two groups that don’t always find ways to intersect but have so much to gain from each other.

• Help women not trained in cinematic techniques be able to tell stories in this powerful medium.

• Showcase our members’ films and publications, as well as new developments in their careers.

-Today, Dazed Digital launches Females First, a video series funding and premiering new work from the best emerging female directors in the world, from art shorts and music videos to documentaries and fashion films. The subject matter will be bold and broad, and all will be created by women.

Research from Online Secondary Research: “US Female Filmmakers”

Statistics on the State of Women and Hollywood

FILM

Women directed 4.7% of studio films from 2009-2013

Women directed 10% of independent films from 2009-20132013

Women Behind the Scenes

- “Women were 16% of the directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers, and editors working on the top 250 domestic grossing films.

- Women directed 6% of the films.

- Women wrote 10% of the movies

- Women comprised 15% of all executive producers.

- Women accounted for 25% of all producers.”

- Women comprised 17% of all editors.

- Women accounted for 3% of all cinematographers.

- Women comprised 2% of all composers.

- Women accounted for 23% of production designers.

- Women comprised 4% of sound designers.

- Women accounted for 9% of all supervising sound editors.

- Women comprised 2% of all special effects supervisors.

- Women accounted for 5% of all visual effects supervisors.

Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film

2012

Women Behind the Scenes

- “Women were 18% of the directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers, and editors working on the top 250 domestic grossing films.

- Women directed 9% of the films.”

- Women wrote 15% of the movies.

- Women comprised 17% of all executive producers.

- Women accounted for 25% of all producers.

- Women comprised 20% of all editors.

- Women accounted for 2% of all cinematographers.

Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film

2011

Women Behind the Scenes- “Women directed 5% of the top grossing films.”

- Women wrote 14% of the top grossing films.

- “Women comprised 18% of all executive producers.”

- “Women comprised 25% of all producers.”

- 20% of all editors were women.

- 4% of all cinematographers were women.

Stats from the Center for Study of Women in TV and Film

2010

Women Behind the Scenes

• “Women directed 7% of the top 250 grossing films.”

• Women wrote 10% of the top 250 grossing films of 2010

• “Women comprised 15% of all executive producers.”

• “Women comprised 24% of all producers.”

• 18% of all editors were women.

• 2% of all cinematographers were women.Stats from the Center for Study of Women in TV and Film

2009

Women Behind the Scenes

- “Women directed 7% of the top 250 grossing films.”

- Women wrote 8% of the top 250 grossing films.

- “Women made up 23% of all producers”

- 18% of all editors were women

- 2% of all cinematographers were women.

Center for the Study of Women in TV and Film, San Diego State U.

2008Women Behind the Scenes

- Only 6 of the top 50 grossing films (12 of the top 100 films) starred or were focused on women.

- “Women comprised 9% of all directors.”

- Women accounted for 12% of writers.

- “Women comprised 16% of all executive producers.”

- “Women accounted for 23% of all producers.”

- Women accounted for 17% of all editors.

- Women accounted for 25% of production managers.

- Women comprised 44% of production supervisors.

- Women accounted for 20% of all production designers.

- Women comprised 5% of sound designers.

- Women accounted for 5% of supervising sound editors.

- Women comprised 1% of key grips.

- Women accounted for 1% of gaffers.

- Women comprise only 23% of film critics at daily newspapers.

- Women comprised 22% of directors working on films appearing at the major film festivals compared to 9% on top grossing films.

- Women accounted for 19% of writers working on films appearing at festivals but only 12% on top grossing films.

- Women accounted for 33% of producers working on films appearing at festivals but only 20% of those working on top grossing films.

- Women comprised 23% of editors working on festival films compared to 17% of those working on top grossing films.

- Women comprised 9% of directors of photography working on festival films but only 4% of those working on top grossing films.

- Overall, women comprised a larger percentage of behind-the-scenes workers on documentaries than narrative features. Of all behind-the-scenes individuals working on documentaries, 29% were female and 71% were male. Of all behind-the-scenes individuals working on narrative features, 18% were female and 78% were male.”

2007

Behind the Scenes- “In 2007, women only comprised 15% of all directors, executive producers, writers, cinematographers, and editors working on the top 250 grossing films.”

- “In 2007, only 6% of the top 250 grossing films were directed by women.”

- In 2007, only 5 of the top 50 films starred or were focused on women.

Sundance Research for Film Screened at the Festival From 2002-2012

- “29.8% of filmmakers (directors, writers, producers, cinematographers and editors) were female.”

- 23.9% of the films in this study were directed by women.

- Films directed by women feature more women in all roles. There is a 21% increase in women working on a narrative film when there is a female director and a 24% of women working on documentaries.

- Females direct more documentaries than narrative films – 34.5% vs 16.9%.

International Study of Films Released Worldwide (G,PG, PG-13 films released 2010-2013)

- Out of 1,452 filmmakers, 20.5% were women, but just 7% were directors. 19.5% of the writers were women, as were 22.7% of the producers.

- The Center found that women accounted for 16 percent of all directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers and editors for the top 250 domestically made films in 2013. That reflects a 2 percent drop since 2012 and a 1 percent decline from the 1998 rate. Hovering at 25 percent, the count of women producers was unchanged, according to the study, which, for the first time, also took a census of female composers, production designers, sound designers, special effects supervisors, supervising sound editors and visual effects supervisors.

-

In terms of behind-the-scenes absence in those categories, 99 percent of films had no female special effects supervisors; 97 percent of films had no female composers, sound designers or sound editors; and 91 per cent had no women as visual effects supervisors. (Women accounted for 23 percent of all production designers working on the top 250 films in 2013, a spike of 3 percent since 2008, when the center also collected data in that category.

-

By comparison, 4.4 percent of the 100 films with the highest box of finance receipts were directed by women during the previously studied decade.

– For the first time at a U.S. competition for movies that were dramas, 50 percent ofnarrative directors at Sundance in 2013 were women.– Of the 1,163 content creators working behind the camera on 82 U.S. films at Sundance in 2013, 28.9 percent were women and 71.1 percent were men. Broken down by storytelling genre, 23.8 percent of content creators in narrative films and 40.4 percent in documentary films were women.– Of the 432 fledgling filmmakers in a year-long Sundance Institute training andmentoring fellowship between 2002 and 2013, 42.6 percent were female. Womencomprised 39.3 percent of the fellows in the Feature Film Program and 54.5 percentof the fellows in the Documentary Film Program.– Based on responses from 34 filmmakers and film industry decision-makers at the 2013Sundance Film Festival, University of Southern California researchers concluded that32.1 percent of personal traits deemed as markers of a successful film director weremasculine and 19.3 percent were feminine, according to USC’s update of a 2012 reporton the prior decade’s female presence at Sundance. (The remaining, perceived traits of successful directors were gender-neutral.)Research from “Online Secondary Research: Around the world”– Each year at the film festival, Women in View releases a report on gender equality in the film and TV industry, and revealed statistics this week, they say, that show the situation getting even more unbalanced: the report’s statistics show Telefilm Canada invested less than six per cent of its feature film funding in 2013 to productions directed by women.Among the recommendations presented by the summit:

‰ That public investment in media industries include a requirement to demonstrate media balance.

‰ That government agencies funding media development report yearly to the public on gender and racial representation in spending, including tax incentives.

‰ That government policy should seek to promote equitable employment of women in TV and film, both on screen and behind the camera.

– ‘A career in the film industry may periodically require 12-hour workdays and is therefore difficult to combine with normal family life. This pulls many women out of the industry. Instead they might go into teaching.’ ‘There is no gender equality agenda for the Finnish film industry. If women do well in the statistics, it’s either a mere coincidence or something that individual women have accomplished all by themselves.’– In 25 of the 98 Nordic fiction films released in 2012, the lead actors, directors, producers and scriptwriters were all men;

In only one of the 98 films were all these positions held by women;

The most gender balanced position is the producer in the Swedish and Danish sectors.-It’s an event dedicated to women in film – and this year the Birds Eye View Film Festival in London focuses only on features made by Arab female directors.The reason for this, according to its programme director Elhum Shakerifar, is that their work is currently on a size and scale unmatched elsewhere.“There’s a new wave of film-making in the Arab world, and women are at the front of it.

– Women are challenging oppression, inequality and corruption – from this, stories are born”

Yet the Doha Film Institute in Qatar, which funds local film-makers, reports that 42% of all its grants since 2010 have been to women, and that last year a third of all films shown at the Doha Tribeca Film Festival were by female directors.

-The cultural landscape is changing in the Middle East, the Arab Spring gave power to the people and women are challenging oppression, inequality and corruption – and from this, stories are born.

“It’s not an established industry either, as in the West, and that can make it easier for a woman to get a breakthrough.”

-From the auteur to the avant-garde, Hong Kong cinema has a strong tradition of women working behind the camera. Perhaps surprisingly, most of their work has rarely been seen in the UK.

– On being female:

Ivy Ho: I think I can speak on behalf of all Hong Kong female directors: we know our place. In big movie productions, all we’re supposed to talk about is romance. They’re even wary of letting women directors do screwball comedies because they think women can’t handle the vulgarity. Sometimes you can venture into men’s territory, like action or suspense films, but you have to try twice as hard.

I hope Kathryn Bigelow would make a difference but I doubt it. People said yes, she did it, but look at her film — it’s a limited release.

Heiward Mak: I don’t think I would categorize myself as a ‘female director.’ I think the film circle is very fair. It’s not necessarily split by the sexes. If someone thinks my work is feminine then that’s just their point of view. It is not a definitive judgment.

Clara Law: I won’t call myself a ‘female director.’ I think everyone has a female side to them, and a male side.

I think [the imbalance] is because of practical reasons. Women are probably not very interested in doing action films. In my case, I’ve never been interested in action films. I’m only concerned with finding stories that interest me.

– The number of women filmmakers, scriptwriters, producers and technicians grows in West Germany. Contrary to their better-known male colleagues’ preoccupation with the exotic and the allegorical, these women directors tend to make films in fictional modes. In such films, the self is clearly inserted, or they address women’s immediate oppression in contemporary West German society. To some extent these films can be called women’s films or feminist films.

– West Berlin, in particular, has emerged as a center for feminist film production and cinema studies. There in November 1973 the first German women’s film festival and workshop was held. Although women have not organized another festival on that scale, non-commercial cinemas and film societies have become increasingly willing to show features by women, and some have even showcased individual filmmakers or organized thematic groups of films around women’s issues.

-In December, 1979, an association of women filmworkers was established in West Berlin (Verband der Filmarbeiterinnen). The organization distributed a manifesto at the Hamburg Film Festival (1979) demanding that 50% of all film subsidies go to women filmworkers and special money go toward distributing and exhibiting films by women.

-only 16% of European films, from 2003 to 2011, were directed by female directors. The Federation of European Film Directors (FERA), who requested this study, is now calling for concerted action by the new European Parliament and Commission.

Research from “Online Secondary Research: UK Female Filmmakers”

– It is historically a man’s genre when it comes to filmmakers; a fact that Warp Films recognised when they set up their Darklight initiative back in 2006. The leader of this development programme, Caroline Cooper-Charles, saw how women were being ‘excluded as audience members as well as filmmakers’ and came up with a very specific target for the scheme: to get more women making horror films in the UK.

The Birds Eye View Festival will be showing a programme of horror shorts directed by women filmmakers on Saturday 12 March at the ICA (London) as part of their ‘Bloody Women’ strand.– Most filmmakers are making their most important films in their thirties and forties, a time when women may be engaged with childrearing and so unable to undertake the heavy commitments needed to make a feature.– She is not interested in taking part in schemes aimed exclusively at women directors and won’t be bestowed or lumbered with the female filmmaker tag: ‘Kathryn Bigelow’s strength is that you don’t know that she’s a woman… I wouldn’t be doing my job if you could tell which gender directed the film.’

Between 2007 and 2010 just 11.8% of UK films released were directed by women.

2011 BFI Statistical YearbookIn an extended list of the critics’ Top 250 Films of All Time only 7 were directed by women.

-In 2012, only five of the top 100 films at the Australian box office had a female director. Just one of these films was solely directed by a woman, the other four were co-directed by a man.

– Of the 20 top grossing films of 2011 in Germany (accounting for more than 20 million sold tickets) only 1 was directed by a woman.

Around 20% of all the feature films made in Sweden are by women.

Only 29 percent of feature films granted funding by SFI (Swedish Film Institute) in 2009 were directed by women.

-Between 2000 and 2009 women directors were responsible for 23 percent of feature film debuts in Sweden.In over 80 years only one woman has ever won the Academy Award for Best Director – Kathryn Bigelow (2009 – The Hurt Locker).

At the 2010 and 2012 Cannes Film Festivals there were no women directors shortlisted for the Palme d’Or. The highest number of women directors who have been shortlisted is four (20%), in 2011.

-Directors UK and the BBC are piloting two new workshops aimed at women directors returning to work after a career break or repositioning their directing career. The workshops will offer advice and guidance to women directors returning to work or who are seeking a renewed impetus, with tips and techniques on how to re-launch, maintain and develop a successful freelance directing career following a break. At the end of each there will be a networking event giving the directors an opportunity to meet with key BBC Commissioners and Executives.

-This morning, the BFI announced the key findings of it’s Statistical Yearbook, which annually presents the most comprehensive picture of film in the UK as well as the performance of British films abroad.

– This year’s report, which draws on data from 2012, showed that UK women film writers declined from 18.9% of the total writers in 2011 to 13.4% (25 writers) in 2012, the second-lowest number in five years.

Even more worryingly, women accounted for just 7.8% of directors on UK films in 2012, a decrease of more than 7% year-on-year (15% in 2011). This translates into 165 male directors and 14 female directors, and puts women directors in film almost on a par with the 8% of female directors currently working in TV drama as revealed by Directors UK earier this year.

22.2 The gender of writers and directors of UK filmsSince 2007, we have been tracking the under-representation of women among screenwriters and directors of UK films.Of the independent UK films released between 2010 and 2012, just 16% of the writers and 11% of the directors were women. However, for the top 20 UK independent films over the same period, women represented 37% of the writers and 18% of the directors. And for profitable UK independent films, 30% of the writers were women.Successful female writers and directors of independent UK films over this period include: Jane Goldman (The Woman in Black and Kick-Ass), Debbie Isitt (Nativity 2: Danger in the Manger), Phyllida Lloyd and Abi Morgan (The Iron Lady), Dania Pasquini and Jane English (StreetDance and StreetDance 2), and Lucinda Whiteley (Horrid Henry: The Movie).In 2013, of the 155 identified writers of UK films released during the year, 22 (14%) were womenThe proportion of female directors in 2013 was higher than in 2012,–Beryl Richards, a director and chair of the Directors UK Women’s Working Group, said the lack of women involved in the British film industry was “appalling, but just not generally noticed”. She explained that there was a correlation between the unrepresentation of women in the top 200 films and the fact they are in the action, thriller and fantasy genres. “There’s significant gender stereotyping and misconceptions about who’s allowed to direct in which genre. Women just don’t get access to those areas of film.”-Lauzen says women are now well represented in US film schools, while Neil Peplow, of the UK training organisation Skillset, says women make up around 34% of directing students in Britain. That translates into a large number of female graduates making short films, but few moving on to features.There are signs that this culture is changing. A 2009 report – carried out by the UK networking organisation Women in Film and Television (WFTV) and Skillset – found that, while “a number of older participants reported direct experience of overt sexism, none of the younger participants [did]”. But Coolidge insists that the film industry – and Hollywood specifically – remains a minefield,-There is also the simple fact that the fewer women there are at the top, the fewer role models and mentors there are; those women who do forge ahead often talk of having to actively ignore the figures.

A lack of female film-makers also seems to have made it difficult for studios to imagine women in charge. Film is big business, filled with financial risk, and so “the whole industry is based on demonstrable success,” says Peplow. “Unless something has worked in the past, it’s very rare that people will take a risk. There’s this perception that, well, traditionally it’s a man’s role, so we won’t buck that.”

The website indiewire.com recently reported that, of the 241 films that had grossed $100m or more in the US over the last 10 years, only seven were directed by women (Shrek, Shark Tale, Twilight, What Women Want, The Proposal, Mamma Mia!, and Something’s Gotta Give).

Bird agrees. “Film directing is more than a full-time job. When you’re making a film, it takes up every day of your life, 16 to 18 hours a day, for a year. Trying to have children and being a film director is virtually impossible unless you’re rich.” Bird doesn’t have children: “If I look deep down inside myself,” she says, “I’m quite sure that I never did it because I never really had time.”

-Looking back to the 1920s, Dinah Shurey was probably Britain’s only female feature film director of the decade, with her lost 1929 film The Last Post currently in the top 10 of our Most Wanted list.

-Alarmingly, the 1960s, that decade of social upheaval and early women’s liberation, brought few opportunities for British women behind the camera (Joan Littlewood with the 1962 Sparrows Can’t Sing is a rare exception).

-Based on the comic opera by Gilbert & Sullivan, Ruddigore was originally commissioned for American television but released theatrically in the UK, making it only the second animated feature to be made in Britain. The first was 1954’s Animal Farm, which was co-directed by the same remarkable lady, Joy Batchelor. To emphasise how exceptional this is, there would not be another British animated feature directed by a woman until Sarah Smith’s Arthur Christmas in 2011.

-It was not until the early 1970s that feminism and women’s consciousness began to influence the production, exhibition and distribution of film and television, as well as education and the emerging film theory. In 1972, the Edinburgh Film Festival included a women’s section for the first time. Women began to engage in debates about their position in society and the ways women were represented in film, television and advertising. Using film and television as a communication tool to meet and educate women, groups like the London Women’s Film Group began working within communities in regional locations.

-The 1980s brought increased awareness of discrimination against women technicians and pressure on institutions such as the British Film Institute to support women’s work. Through the BFI’s education department and production fund there was some temporary support for British feminist films and funding for feminist distributors.

-The BAFTAs and the Oscars do reflect one truth, however: in the world of major Hollywood feature films, women account for just five per cent of directors. (That rises to 22 per cent of Sundance feature films, and nearly half of Sundance documentaries.)

-“There’s a notable gap between the amount of women making shorts and those established in features, and at the top of the industry I think there’s still a resistance towards new female talent. There’s a dominance of male directors and producers, and has been for some time.”

-On Tuesday 11 November, the fifth UnderWire Festival will open at The Yard in Hackney Wick. Founded by Gemma Mitchell and myself in 2010 with the aim to foreground female filmmaking talent, the opening night’s screenings are always of the XX Award Category. Unique to UnderWire, films selected for this award are of women’s stories and feature female characters at their core.

-Throughout the programme are stunningly diverse fiction, documentary and animation films. The festival has grown from six categories in the first year, to 10, recognising female talent in editing, cinematography, sound design, composing, writing, directing, producing, and acting, together with a special BFI Future Film Award for Under 25s.

– Birds Eye View Film Festival was the vision of Rachel Millward and Pinny Grylls as a response to the industry numbers indicating that men directed 92% of films on general release. They set out to create a festival that celebrated female filmmakers.

-’Three years later, Birds Eye View launched its international film festival in 2005, and over the next several years showcased some of the world’s best female filmmaking talent.

-Over the last 12 years BEV has developed a number of partnerships including events with Oxfam, Whistles, Southbank Centre and WOW Festival and media partnerships including Marie Claire and Moviescope. Guest speakers at the festivals have included Juliet Stevenson, Gillian Anderson, Zoe Wanamaker, Rosamund Pike, Hayley Atwell and in 2013, Jodie Whittaker who declared that ‘women are not a genre.’BEV consistently champions female filmmakers and the need for equal representation behind and in front of the camera. In 2013 the festival had a specialist programme celebrating Arab female filmmakers including an International Woman’s Day preview of Wadjda by Haaifa Al-Mansour and the UK premiere of When I Saw You by Palestinian filmmaker Annemarie Jacir.

Research from “Online Secondary Research: More Statistics”

– In 2013’s top-grossing movies, women accounted for only 16 percent of important positions behind the scenes, including directors, writers, executive producers, producers, cinematographers, and editors.

- Women make up only 23% of crew members on the 2,000 highest grossing films of the past 20 years.

- Only one of the top 100 films in 2013 has a female Composer.

- In 2013, under 2% of Directors were female.

- The only departments to have a majority of women are Make-up, Casting and Costume

- Visual Effects is the largest department on most major movies and yet only has 17.5% women

- Of all the departments, the Camera and Electrical department is the most male, with only 5% women

- Musicals and Music-based films have the highest proportion of women in their crews (27%).

- Sci-Fi and Action films have the smallest proportion of women (20% and 21% respectively).

- The films with the highest percentage were “Mean Girls” and “The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants” (42%).

- The most male crews were “On Deadly Ground” and “Robots” (10% female).

- There has been no improvement in the last 20 years. The percentage of female crew members has decreased between 1994 (22.7%) and 2013 (21.8%).

- The three most significant creative roles (Writer, Producer and Director) have all seen the percentage of women fall.

- The jobs performed by women have become more polarised. In jobs which are traditionally seen as more female (art, costume and make-up) the percentage of women has increased, whereas in the more technical fields (editing and visual effects) the percentage of women has fallen.

On average, women make up 22.6% of a film crew

-In fact, in 1994 the average percentage of women on a film crew was 22.7% and by 2013 it had actually shrunk slightly to 21.8%.

-The three most significant creative roles (Writer, Producer and Director) have all seen the percentage of women fall over the past 20 years.

-There are many reasons why the under-representation of women in the film industry could be seen as a problem. These include female crew members finding it harder to get hired/paid, employers selecting workers from a pool that is half the size it should be, fewer female role models for aspiring creatives and, of course, justice/ equality/ fairness.

-The report shows that just 16% of behind the scenes personnel – directors, writers, executive producers, producers, editors and cinematographers – staffing the top 250 grossing films of 2013 are women. Last year’s report put the figure at 18%; which was itself a small increase on the year before. To underscore how little progress there has been, 16% is lower than the figure for 1998, the first year the Celluloid Ceiling report appeared.

-Other than cinematographers, none of the major job types saw a rise, with only producers holding steady at 25% – itself the biggest category for women. Production designers and editors were the next largest percentage share for women, at 23% and 17%.

–• Directors: 6%, down 3% from 2012

• Writers: 10%, down 5% from 2012

• Producers: 25%, even with 2012

• Executive producers: 15%, down 2% from 2012

• Editors: 17%, down 3% from 2012

• Cinematographers: 3%, up 1% from 2012

• Production designers: 23%, up 3% from 2008 (when the stats were last compiled)

• Sound designers: 4%, down 1% from 2008

• Supervising sound editors: 9%, up 4% from 2008

• VFX supervisors: 5%-In total, women accounted for 16% of the 2,938 people employed on the pics surveyed. The largest share of female employment came as producers, editors and production designers. Women were most likely to work in drama, comedy, and documentary films, and least likely to work in animation, sci-fi and horror titles.

– Figures seen by the Guardian have revealed that gender disparity is entrenched in the film industry, where more than three-quarters of the crew involved in making 2,000 of the biggest grossing films over the past 20 years have been men, while only 22% were women.

-The report showed that rather than improving over time, the number of women working with blockbuster film crews in 2013 actually declined from previous years, to an average of just 21.8%. Fewer than 2% of the directors of the top 100 grossing films last year were female and only one had a woman to compose the score.

-The three blockbuster films with the highest female contingent in the crew were revealed to be Tina Fey’s cult classic Mean Girls, The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, and Honey – each of which had a workforce composed of 42% women. Steven Seagal’s On Deadly Ground had the lowest representation of women, with a 90% male film crew.

Kathryn Bigelow has been the only woman to have won a best director Oscar, for The Hurt Locker, in 2009.

The British Film Institute, which helps the industry, handing out £27m a year, said it was trying to tackle the diversity issues; new funding quotas were being introduced in September which would stipulate that films, to be eligible for BFI funding, should have a certain percentage of actors and crew who were female, gay, disabled and from ethnic minorities.

– Women filled 26% of key behind-the-scenes roles – directors, producers, executive producers, writers, editors and cinematographers – in feature-length films shown at leading film festivals over the past year, according to the survey, Independent Women, sponsored by the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University.

– Independently produced films, which typically have lower budgets and skirt Hollywood hierarchy, have consistently kept the door ajar, if not fully open, to women. The findings, based on more than 9,000 credits at 23 film festivals from March 2013 to April 2014, were similar to a previous study in 20011/12. The 26% figure was a modest advance from the 24% recorded in 2008/9.

Research from “Online Secondary Research: Women Director’s Examples”

Highest-Grossing* Movies Directed by Women (Since 1980) Title Director Year Metascore Users U.S. Gross* 1 Shrek Vicky Jenson 2001 84 8.6 $376.0m 2 Look Who’s Talking Amy Heckerling 1989 51 n/a $277.0m 3 What Women Want Nancy Meyers 2000 47 6.3 $263.1m 4 Dr. Dolittle Betty Thomas 1998 46 5.6 $244.4m 5 Sleepless in Seattle Nora Ephron 1993 71 9.6 $243.3m 6 Deep Impact Mimi Leder 1998 40 3.6 $238.1m 7 Wayne’s World Penelope Spheeris 1992 53 9.8 $233.1m 8 Alvin & the Chipmunks: The Squeakquel Betty Thomas 2009 41 5.3 $225.0m 9 Big Penny Marshall 1988 70 7.4 $222.4m 10 Twilight Catherine Hardwicke 2008 56 5.6 $213.4m Research from “Online Secondary Research: Feminist Filmmaking”

– First on the menu was a Wikipedia editing workshop, where, assisted by three Wikimedia trainers, we created or updated Wikipedia pages for feminist filmmakers, films and organisations. All 18 contributors proved themselves perfectly capable of mastering Wiki markup (no, it really isn’t that hard but doesn’t it sound good?) and in three hours we created lots of new exciting feminist Wiki content.

– Today, of the hundreds of films that traveled on an international women’s film festival circuit, as well as throughout college campuses and community centers, a mere handful are available in digital format. Most of the distribution networks that carried feminist films folded decades ago.

-Perhaps a diffused and unwieldy concept today, in the U.S., U.K., and Canada in the early seventies, the notion of “women’s cinema”17 was a breakthrough idea. For the first time, “women’s films” denoted films made by and for, not just starring or about, women and emerging out of the political fever and radical demands of the women’s movement. Exhibition of these films began in earnest on a new “women’s films” festival circuit where it became readily apparent that the relationship between women and cinema was about to shift for good.

– The decade of the seventies witnessed a veritable explosion of what I would like to embrace as “feminist cinema” and the production of an unprecedented number of films by, for, and about women. One scholar of the Feminist Film Movement claims that before 1969 fewer than 20 “feminist films” existed whereas by mid-decade, in 1976, over 250 films by women circulated, and the number of feminist filmmakers had risen from less than 40 in 1972 to more than 200 in 1976.18 Quite unlike the increasingly solitary viewing practices that are taking hold in the twenty-first century, in the seventies, female audiences filled auditoriums, classrooms, and town halls as films made by women began to circulate as a result of newly forged distribution collectives such as New Day Films, Iris Films, and the Women’s Film Coop.

-The bias in feminist film theory towards avant-garde and formally experimental films as the most successful instantiations of “alternative,” “counter,” or “feminist” films emerged in the seventies and continues to hold intractable influence. As a result, the illusion of a consensus about what constituted “feminist films” in the seventies has developed in the academic discipline to the lamentable detriment of the rich variety of filmmaking practices that actually made their way to diverse audiences at that time.

-The surprising fact is that the majority of films made by, for, and about women in the seventies were documentaries.

– Ireland’s Feminist Film Festival is running for the first time this autumn in Dublin.

• To screen, support and promote films where women have played a vital role in a film’s making, production or as a crew member in order to help counter the under-representation of women in the film industry.

• To help counteract the mis-representation and narrow range of women portrayed through stereotypical female characters and in two-dimensional roles and expose audiences to a broader scope than those often found in mainstream cinema.

• To bring the perspectives, stories and experiences of women, feminists and *women-identified people to a !wider audience through film in an inclusive, positive and friendly environment and event

– WHY A FEMINIST FILM FESTIVAL???

*Of the top 2,000 biggest grossing films over the past 20 years…

- Women accounted for only 13% of the editors, 10% of the writers and just 5% of the directors

- More than three-quarters of the crew have been men, while only 22% were women

- Visual effects, usually the largest department for big feature films, had an average of only 17.5% of women, while music had just 16%, and camera and electricals were, on average, 95% male

My Primary Research questionnaire:

- 80% of women said they would like to go into the media industry, while 20% said no, as they thought it would be too hard to progress in.

- However, 75% of men said they would, and 25% said they didn’t know.

Interestingly, the results didn’t seem to be conclusive about whether people thought there were as many opportunities in the media industry for women as for men:

- 45% of people said there are as many opportunities

- 45% of people said there aren’t

- 10% said they didn’t know

When asked to name 3 Female film directors/producers 5 people skipped the question, which is 25% of people. Of those who did answer 3 said they didn’t know any (15%), 4 people could only name one (20%) while 7 of those answers were actresses who were also directors (35%), which could show a trend. However, 45% of people could answer with 3 female directors/producers which is more than I expected.

When asked to name 3 Male film directors/producers only 2 people skipped the question (10%) 5% of people only named one male film director and another 5% naming only 2, with no one answering the question to say they didn’t know any. This means that 80% of those interviewed knew the names of 3 male directors.

When asked if 75% of blockbuster crews being male shows an equality problem in the industry:

- 65% said yes

- 25% said no

- 10% said I don’t know

Finally, the last question on what kind of infographic people would rather watch had very similar answers and did not give a conclusive result.

- 26.32% said The current status of women in film

- 26.32% said Gender equality in film

- 26.32% said The history of women in film

- 21.05% said Feminist filmaking

Research from “Information from Chosen Books”

– “In the 1910s and early 1920s the American Film Industry offered women opportunities that existed in no other workplace”

“In any given production the screenplay was likely to have been penned by a women, as was the continuity script, the step-by-step guide outlining all production activities. A female director may have guided the female star, who often worked for her own production company. Some women did it all. Lois Weber, the most famous female filmmaker of this period, was a screenwriter, actress, director, and producer, often on the same project. After the shooting ended, a women may have edited the film, a female editor may have re-edited it, a female exchange owner may have distributed it, and a female manager might have exhibited it in her theater.”

‘By the mid-1920s, female directors and producers, many of whom were critically acclaimed and commercially successful, found themselves defined as unfit.”

-“The battle-fields of the film industry are still strewn with stifled ambitions of women directors who only manage to produce one film.”“Whereas in the 1970s we needed an embattled stance, and searched for female directors who obviously challenged and resisted dominant male cultures, now it is clear that being “female” or “male” does not signify any necessary social stance vis-a-vis dominant cultural attitudes.”

“The point is that Western culture has constructed active and passive “positions” for “male” and “female”. But people can take up cultural/psychic places that differ from the ones officially assigned to their sex, and it is this fact that makes it possible to envision progressive social change where the gender is concerned.”

-“Women directors, almost invisible just 15 years ago, have from the late 1970s on, and especially in the 1980s, been entering feature filmmaking in unprecedented numbers.”

“It is no longer unusual for five or six films by women directors to be playing simultaneously in Manhattan theaters, films as often from Europe or elsewhere, as from America, as the phenomenon is international”.

-“The term women’s cinema, or more precisely, the women’s film, has acquired another meaning, referring to a Hollywood product designed to appeal specifically to a female audience. Such films, popular throughout the 1930s, ’40s, and 50’s, were usually melodramatic in tone and full of high-pitched emotion.”“As Mary Anne Done has argued, the “woman’s film” identifies female pleasure in the cinema as complicit with masochistic constructions of femininity”.

“Even while a critic such as Molly Haskell condemns the facile pathos of the women’s film, she wonders why it is that the emotional response should be so devalued as to be relegated to an “inferior” genre.”